By: SKIP BANDELE

LONG BEFORE Britain’s yeomen decided to accept the King’s shilling and fight battles that did not really concern them one way or another on his behalf, a uniform dress code had, and has subsequently played an important and omnipresent part in maintaining law and order in our society.

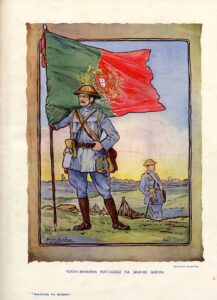

Varyingly seen as a mark of respect, authority or even kinship (esprit de corps), the wearing of the same clothes transcends history, most commonly identified with the military or police forces, although sporting the same look is also popular amongsocial subcultures and classes, workforces, and still an obligatory necessity at many schools not only restricted to the British Isles.

I suspect that the custom originated during some long forgotten conflict as a means of separating the two warring factions, preventing those involved from turning on and killing one another. Today, tribalism still plays an important roll in this identification process, uniformity instilling a sense of belonging if not a loss of individuality.

Having been forced to spend my formative years wearing ties, shirts and blazers I personally suffer from ‘uniform aversion’, and from another phobia, namely that to authority. Somewhat paradoxically in the context discussed so far, the two do go together. Wearing the wrong colour socks (perhaps I did exaggerate my one-boy protest somewhat by choosing luminous orange or fluorescent green) earned me many a detention spent contemplating the right to freedom of expression.

A recent study suggests that wearing a uniform improves pupils’ behaviour both inside and outside school, reduces bullying and instils a sense of responsibility in the local community. These findings do not correspond with my experiences.

Uniforms

My period of incarceration at a supposedly ‘posh’ grammar school was characterised by swearing, shoplifting outside the gates (I did not) as well as constant physical and mental violence directed at fellow class mates within, not least involving my person for having committed the crime of being the only German student among 800 boisterous English boys.

Speaking of which, did you know that calling any public servant in Germany, be it post office worker, traffic warden or policeman, anything only slightly derogatory will result in a heavy fine? Which brings me back to uniforms. The sight of the dreaded black Waffen SS or field grey Gestapo outfits in National Socialist Germany instilled terror and fear in all and sundry, guilty or innocent, much as today’s immigration officials do on Britain’s borders.

In fact, the Home Office is so worried that it has now decided that the clothes worn by its representatives at the cutting edge are ‘intimidating’ and should be replaced. Tens of thousands of pounds are to be spent on new suits which look less like a ‘uniform’ in order not to upset failed asylum seekers. Shadow Immigration Minister Damian Green commented: “The Home Office has become obsessed with uniforms because it is easier to change the uniform than the policy.” Sir Andrew Green, Chairman of Migrationwatch UK, added: “This is a difficult area, but we must keep our eye on the ball.” The whole thing reminds me of one of my favourite jokes.

A New York school bus driver (double-decker) becomes so fed up with the black and white kids fighting with each other that he stops the bus one day and storms upstairs. “Quiet!” he screams, “I’ve had it with you lot, from now on you are all green, understood?” Turning on a black boy, he asks: ”What colour are you?” “Green”, came the timid reply. After repeating the exercise with a white boy, the driver commanded satisfied: “Right, the light greens to the front and the dark greens at the back!”

The GNR

The effect GNR patrols have on the law-abiding motorist in Portugal is little better than that of their uniformed cousins elsewhere. Summer driving in the Algarve can be a nightmare even without the additional threat of a militarily clad figure bearing down on you at the dusty roadside, intent on finding something wrong, which they inevitably do.

Anyway, where are they when some idiot is performing a hair-raising overtaking manoeuvre almost resulting in multiple casualties, a car is coming at you the wrong way around in a roundabout or when that infuriating white delivery van is tailgating on the Via do Infante? “At lunch”, I am reliably informed!

It seems that serial traffic maniacs are well informed as regards to duty rosters. Like any self-respecting scribe, I did conduct some background work before sitting down to write this page, with some surprising results. Behind those glaring, coated and forbidding sunglasses, underneath that impeccably ironed uniform and outside those highly polished jackboots, are hiding believe it or not ,perfectly normal human beings trying to instil civic values while earning a pittance of a living.

An ordinary Guarda Nacional da República officer is left with little over 800 euros a month after deductions. That is before mortgage payments, petrol, upkeep and other expenses are taken into account. What remains from a job that often entails serious personal danger, heaps of abuse and little in the way of appreciation has to suffice to finance a life off-duty severely curtailed by the most antisocial shifts imaginable.

As a consequence, once you manage to look beyond that representative and sometimes seemingly repressive symbol of authority, you may very well discover a sensitive person crying out for love and friendship as I did and drastically reduce your stack of speeding tickets in the process!