It is commonly thought that the adulation accorded to pop stars in the 1960s was a new phenomenon. But the 1840s witnessed similar outbursts of crowd behaviour on the appearance and performance of the pianist Franz Liszt.

Ladies fought over his gloves and handkerchiefs and even his cigar butts. Heinrich Heine invented the word Lisztomania for the lady admirers who wore his portrait on cameos or brooches, or carried glass phials into which they poured the dregs from his coffee cup. In those days, the expression -mania indicated a medical condition, and was thought to be contagious.

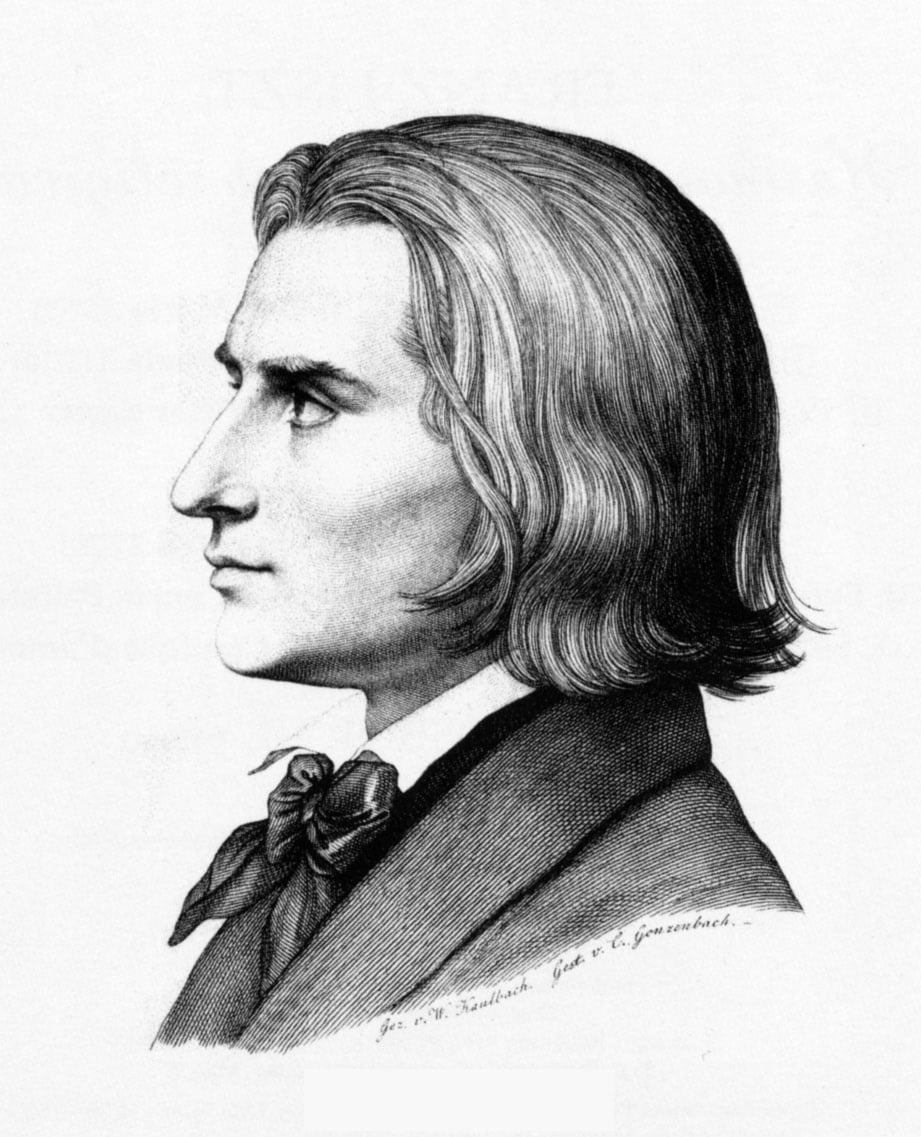

Liszt’s mesmeric personality and flowing mane of auburn hair created a striking stage-presence. And his apparently effortless playing at sight of even the most complicated pieces raised the emotions of his audiences to an ecstatic level. Hans Christian Andersen attended a Liszt recital, and recorded the impression: “I saw that pale face assume a nobler and brighter expression; the divine soul shone from his eyes, from every feature; he became as beauteous as only spirit and enthusiasm can make their worshippers.”

In the pre-railway age, Franz Liszt toured Europe as a performer on the piano, and his years of travel from 1838-1847 saw him perform in hundreds of locations from St Petersburg and Glasgow in the north, to Malaga and Constantinople in the south; Russia, Ukraine and Turkey in the east; and in the west, Ireland, Spain and Portugal.

It is astonishing nowadays to realise that he must have travelled thousands of miles by horse-drawn carriage, often transporting his own piano with him.

The Portuguese invitation

Portugal in the early 19th century looked back with nostalgia to the reign of D João V (1706.1750), possibly the richest of all Portuguese monarchs thanks to the import of gold and jewels from Brazil. He and his son D José enjoyed a predisposition to music, perhaps envied in other European courts.

But the earthquake ruined Lisbon; the subsequent French invasions ruined Portugal; and the recently finished civil war impoverished the nation and its culture. In this country made artistically barren by disaster, a visit by the principal pianist in Europe was to be envied.

Liszt was invited to visit the Portuguese royal family to receive the Order of Christ from Queen D Maria II. Encouraged by Prince Felix von Lichnovsky, nephew of the celebrated patron of Beethoven, he set out from Paris in 1844.

Journey through Spain

On his way to Lisbon, Liszt arrived in Madrid on October 22, his 33rd birthday. He gave four recitals in the Spanish capital, and was paid the enormous sum of 2000 francs per performance. In return for the performance before the 14-year-old Queen Isabella II, she invested him with the Cross of Carlos III, and gave him a diamond studded pin. He gave four further concerts in Madrid, with receipts dedicated to charity.

He journeyed on to Córdoba, then to Seville, where he was open-mouthed at the grandeur of the cathedral. Hearing the cathedral organist playing his 12 Melodías Armonizadas, Liszt was full of praise, suggesting that he had detected a major fault – there were only 12 Melodías, and the organist should compose at least 24. He called at Granada and Cádiz, before embarking on the English steamer Montrose at Gibraltar.

Franz Liszt in Lisbon

He and his entourage arrived in Lisbon on January 15, 1845, accompanied by his friend Louis Boisselot and his secretary, the baritone Ciabatta (an unlikely sounding name). On that evening, he attended a performance of Donizetti’s Lucrezia Borgia at the Teatro São Carlos.

His visit to Portugal lasted six weeks, and his first recital was at São Carlos on January 23, followed by seven more at the same venue. On January 26, he played a private recital for the royal family. The 24-year-old Queen D Maria and her German husband D Fernando treated Liszt as a god, and awarded him not only the insignia of a Knight of the Order of Christ but also gave him a diamond-encrusted snuff-box, which he described as “the most magnificent royal gift that I have ever received”, and, in return, he presented to the Queen a dedicated copy of his Marche Funèbre from Donizetti’s Dom Sebastien. Donizetti wrote to his friend, “Buy Liszt’s arrangement of the March; it will make your hair stand on end.”

The next day, he gave a similar recital for the Prime Minister, Costa Cabral. He also gave a private concert in the home of Visconde do Cartaxo, where he played polkas and waltzes.

On February 12, Liszt gave a public recital for the benefit of the Asilo da Infância Desvalida na Escola Primária do Largo do Carmo.

After the orchestra had been paid, and the management had taken its cut from the box-office receipts, there was precious little for the charity, and Liszt characteristically made up the donation from his own pocket.

Liszt was so popular that he was also invited to become an associate of the Academia Filarmónica. At one recital, he invited the Portuguese pianist João Guilherme Daddi (1813-1887) to share the platform.

Forty-one years later, in the company of the Portuguese Ambassador in London, Liszt asked after Daddi. When he was told of this enquiry, Daddi was overcome to think that the Master still remembered him.

Liszt’s piano

Records show that, in 1809, there were only 12 pianos in Lisbon, but, by 1821, there were more than 500. Not wishing to risk his recitals on possibly inferior instruments, Liszt chose to bring his own piano with him. It was a Boisselot, and it travelled with him from Paris as a part of his luggage.

At the end of his visit, he offered the instrument to the Queen as a gift, and she passed it on to the piano teacher of her children; it is now in the National Music Museum in Lisbon. One of his pupils, José Vianna da Motta, asserted that it was the first grand piano to arrive in Lisbon.

There is a continuing rumour that Liszt performed also in Braga during his six-week stay in Portugal. In view of his engagements in Lisbon, the distance between Braga and the capital, and the necessary travelling arrangements by sea and by coach, it is highly unlikely that such a recital took place.

The reason for such a rumour may well lie in the fact that he did play for Costa Cabral in Lisbon on the Prime Minister’s own piano, and that instrument is now in the Avelar house in Braga, home of a descendant of Costa Cabral.

The return journey

Liszt returned to Spain again via Gibraltar, leaving Lisbon on the steamship Pasha on February 25. He confided in a letter to a friend that, during this tour, he was extremely unhappy. The reason was that his relationship with Marie d’Agoult was becoming acrimonious, and his contact with their three beloved children was becoming more remote.

Making his way northwards, he visited Málaga, Valencia and Barcelona, and left the peninsula in April 1845. He never returned, but many Iberian pianists travelled north to study with Liszt at Weimar, the most famous being José Vianna da Motta, who later became the Director of the National Conservatory in Lisbon.

Liszt’s most famous Iberian work is probably the Spanish Rhapsody of 1863, which sadly has no direct connection at all with his Iberian tour.

By Peter Booker

|| features@portugalresident.com

Peter Booker co-founded with his wife Lynne the Algarve History Association.

www.algarvehistoryassociation.com