Why should we remember this extraordinary king from more than 500 years ago? Why is he known in Portuguese history as the Perfect Prince? Why did the government of Salazar’s dictatorship choose to honour him by portraying him on a banknote? In today’s world of political frustration, where leadership seems a dying art, it is worthwhile to consider the personality of this remarkable man.

Born in 1455, son of D Afonso V, João ascended the throne when he was 26 years old and died 14 years later at the age of 40. In those few years, João stamped his authority on a fractured nation and bequeathed to his successor D Manuel I a strengthened government. Following his expansionist policy, D Manuel soon became one of the richest sovereigns of his age.

Moroccan Conquest

D Afonso V was known as O Africano because of his fixation with the conquest of Morocco. At the capture of Arzila in 1471, he was able to knight the Infante João when the boy was just 16. As king, D João sponsored further expeditions to Morocco in 1485 (Azamor), 1487 (Anafé) and 1489 (Graciosa), the last of which he supervised from the town of Tavira.

Re-assertion of Royal Authority

D Afonso had come to the throne at the age of six and, dominated by an unruly aristocracy, he alienated much of the landed property of the crown. His son João, while he was Infante and heir to the throne, was impeccably loyal to his father, but as soon as he became king, his policy towards the nobles changed.

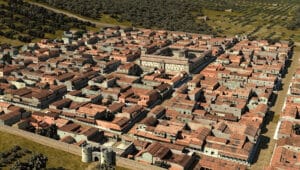

In 1481, he summoned the Cortes to Évora, by all accounts his favourite city. Representatives of the towns and cities successfully petitioned the king to abolish the aristocratic power to interfere in municipal affairs. Of the aristocracy, he demanded written proof of ownership of land, and even when that written proof could be supplied, he often took land back into the royal estate.

More, he demanded that the nobles pay him homage on bended knee. After the chaos of D Afonso’s reign, many nobles had difficulty with this act of submission, in particular the powerful dukes of Bragança and Beja.

The king’s investigator found in Bragança’s papers certain evidence that he was in treasonable communication with the King of Castile. D João had Bragança tried at Évora, and on June 29, 1483, in the centre of Évora, the most powerful duke in Portugal was beheaded.

In 1485, highly suspicious of the Duke of Beja, D João summoned him, and asked what he would do if someone was plotting to kill him. “I should kill him first,” fatally replied the duke, whereupon the king stabbed him to death. Over 80 other conspirators were executed or exiled.

It is not difficult to believe that D João was a well-loved king of his peoples and dreaded by his nobility. D João declared: “Eu sou o senhor dos senhores, não o servo dos servos.” (I am the lord of lords; not the servant of servants), and after these events, D João had very little open opposition from aristocrats.

Portuguese Flag

Every time the flag of the republic is raised today, we pay unwitting homage to this king, because the central part of the flag of the republic was designed by D João II. He arranged the five central shields in their current upright and rounded format and standardized the number of border castles at seven.

Exploration

After the death of Henry the Navigator in 1460, the impetus for southward exploration had lost its champion. The Infante João took responsibility in 1475. Under his guidance, southward exploration continued apace. In 1482, D João founded the fortress of São Jorge da Mina in present day Ghana to exploit the gold trade in West Africa, and in Lisbon the Casa da Mina was in a building next to the river and within sight of the palace, so that he could watch his ships being unloaded.

He sent annual expeditions further and further south along the Atlantic coast of Africa. Diogo Cão was at the mouth of the Congo in 1482, and the southward push continued until Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1487. His ship was the first European vessel to reach the Indian Ocean from the Atlantic.

At the same time, D João sent two overland explorers to the East. Pêro de Covilhã journeyed to India and Persia, East Africa and Egypt. Afonso de Paiva disappeared into Ethiopia. After Pêro had sent a report back to the king, he was instructed to travel south in search of Afonso de Paiva, and he was then unavoidably detained in Ethiopia. A description of their eastbound journeys was presented by Camões in his majestic epic, the Lusíadas. When da Gama reached India in 1498, he knew to make for Calecut, probably because of Covilhã’s written information.

It is thought that from 1487 onwards, D João commissioned further secret surveys of the South Atlantic, and that before the negotiation of the treaty with Castile in 1494, he already knew of the existence of the territory we know as Brazil.

The Treaties

D João reached agreement with Castile in two treaties. During his father’s reign, the Treaty of Alcaçovas in 1479 ended the war with Castile, and also determined that all new discoveries made south of the Canary Islands would belong to Portugal. When Columbus returned in 1492 from his famous voyage, with the news that the Caribbean Islands were south of this line, the treaty was re-negotiated and signed at Tordesilhas in 1494.

D João insisted that the north-south line dividing Portuguese and Spanish discoveries should be not 100 leagues but 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands. This line included the eastern part of today’s Brazil, and if it had not been for his insistence, Brazilians would today speak Spanish and not Portuguese.

Death

D João had never enjoyed robust health, and it appears that he suffered from stress. After the ratification of the Tordesilhas treaty, he was feeling unwell and, suspecting that he was being poisoned by aristocrat opponents, he travelled south to Monchique to take the waters. He moved on to Alvor, where he died. He was buried first in Silves Cathedral and, after a year, D Manuel personally supervised his exhumation and removal to Batalha.

Legacy

D João bequeathed a strong centralised state as he had dispossessed the nobility; he supervised the surge in Portuguese exploration from which his successor became immensely rich; and he ensured that the Brazilian part of South America would be Portuguese and not Spanish.

In a series of banknotes, Salazar paid homage to the famous explorers as well as to their guide and employer, D João II. And today, every time the flag of Portugal is raised, we are all paying our respects to this exceptional monarch.

By Peter Booker

|| features@portugalresident.com

Peter Booker co-founded with his wife Lynne the Algarve History Association.

www.algarvehistoryassociation.com