This second article discusses the main women in Salazar’s love life, and there were certainly many other women of lower prominence than those mentioned here. Although Franco Nogueira asserted that Salazar had intimate relations with more than one woman, nothing has been proved beyond doubt.

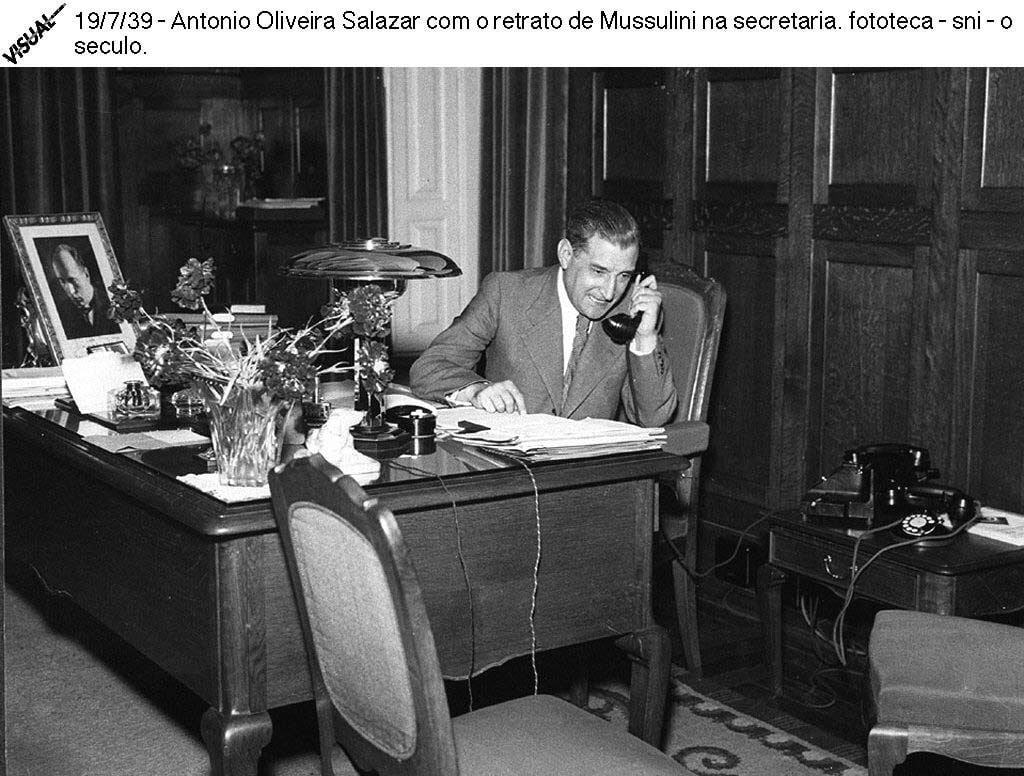

In last month’s article, I posed three questions. First, how was it possible to keep the Portuguese people ignorant of these affairs until well after Salazar had died? We must not forget the power of state propaganda and strict censorship. It is astonishing that the unworldly Salazar, until 1928 a university academic, should have been able to manipulate the state propaganda machine so effectively.

Second, how was it that the pupil of a seminary, an austere solitary who nearly became a priest, followed a love life that was so sensual, so free and yet so secret? We must conclude that Salazar was graced with a powerful libido, and he was attracted to women until well into his 60s.

Even at the age of 16, he was attracted to Felismina, and we conclude that this discovery of sex was perhaps one reason why he decided not to become a priest. He was not a Don Juan, since he treated most of his loves with consistent courtesy and corresponded with them over many years. Although he was a regular attender at Mass, his behaviour leads us to believe that he had lost his faith early in life.

Third, in an age when marriage was the norm, how is it that Salazar never tied the knot? The usual explanation was that he was married to the country, so that he could devote his whole life to its government and to responding to its many needs.

This concept proved to be pure propaganda. Many other contemporary statesmen were married and there is no evidence of any distraction from their duties caused by their domestic relationship.

He had enough time to meet his many girlfriends and he carried on a considerable correspondence with many of them for years. Perhaps he never found the right woman, although he appeared at many official functions with the aristocratic Carolina Asseca.

She certainly wrote letters in which she professed her love for him. But the more likely explanation is that it was Salazar himself who avoided marriage with Carolina because he feared political interference and pressure from her powerful and rich family.

Salazar met his girlfriends in the most varied places. Their meetings took place in his first lodging in Lisbon, or the women’s homes or in hotels, and when he was President of the Council, he also received them at his official residence at Palácio de São Bento, or at his summer residence at Forte de Santo António da Barra in São João do Estoril. This means that Salazar met his girlfriends in the places that suited him best and he had no problem doing so in the residences that the State allocated to him.

Felismina de Oliveira (1905)

His first love was Felismina, whom the 16-year-old Salazar met at Viseu railway station when she was 18. Salazar was studying to be a priest at the time and attended the seminary in Viseu, but that fact did not prevent him from beginning a love affair. She was a friend of Marta, one of Salazar’s sisters, and during the long holidays, Felismina would stay at the Salazar family home in Vimieiro. They exchanged innumerable letters.

Felismina began to have problems of conscience regarding her relationship with Salazar. She was a devout Catholic and did not want Salazar to renounce the priesthood because of her. Little did she know that not only was Salazar already thinking about abandoning this career, but that he was also about to dump her. He found an easy way out by proposing that they remain friends and later convinced her to collaborate with his regime. As a loyal informant, Felismina also became a fanatical supporter of the Salazar dictatorship.

Thanks to her political contact, Felismina’s career as a primary teacher was rewarded by promotion to primary school inspector. And she continued to love Salazar all her life, convinced that he also continued to love her and that he had not married her first for the sake of God and second for the sake of the country.

Júlia Perestrelo (1916)

Salazar tired of Felismina because he was courting a wealthier girl, Júlia Perestrelo, the daughter of the owners of the Vimieiro farm where Salazar’s father was a manager. Employed to give her private tuition, Salazar fell for Júlia, and started to exchange messages with her. The richer Perestrelo family made him see that, despite the fact that he had a first-class degree in Law, his lower social status was unacceptable to them.

Glória Castanheira (1918)

While still at the university in Coimbra, Salazar met Glória, an amateur pianist. She may have seen him as a spoiled young man, but he spent many evenings at her house. Their correspondence lasted for a further 38 years.

Maria Laura Campos (1932)

In his first years as President of the Council, Salazar opted for the eccentrically dressed Maria Laura. At that time, the 39 years old Salazar transformed his dark rented room into a lighted romantic alcove, and they frequently met there. Although married, she had various lovers, and possibly added Salazar to her list at that time.

Their relationship persisted even while Maria Laura divorced and remarried. There were ups and downs in this relationship since Maria Laura was a spendthrift and Salazar was so miserly that he was called “Botas” (Boots). As the relationship with Maria Laura ended, there was no problem for our gallant President of the Council as, shortly afterwards, Salazar befriended another woman, Maria Emília Vieira.

Maria Emília Vieira (1934)

Maria Emília was a dancer and astrologer and was a modern, fashionable woman with a charming smile. Salazar really enjoyed her company, and even told some of his closest friends that she was his favourite guloseima (literally ‘dainty titbit’). He also appreciated Maria Emília’s skills as an astrologer and consulted her about any important decision, even in politics. It appears that Maria Emília’s horoscopes played an influential part in the country’s destiny for at least three decades.

Maria Emília must have been a captivating woman since she was seeing both Norberto Lopes and Salazar at the same time. The journalist Norberto Lopes was director of two very important daily newspapers, Diário de Lisboa and A Capital and was also one of the main figures in the democratic opposition to Salazar’s dictatorial regime. But both men courted the same woman over some time. Eventually, Norberto Lopes married her, but the love triangle continued, with the knowledge of all those involved.

Carolina Asseca (1945)

When in May 1945, Salazar invited the ex-Queen D Amélia de Orleans to tea at São Bento, he also invited a number of ladies who had been familiar with court life before the Implantation of the Republic in 1910. The most intriguing was Carolina Asseca, who had accompanied D Manuel II into exile.

Anglophone, rich and refined, she was 10 years younger than Salazar and had been widowed at age 23. He sent her many of the flowers which arrived unasked at his official residence, and for some years lunched with her on Saturdays and Sundays at her home in Sintra.

It was rumoured that they were engaged, and many former aristocrats found reason to hope that this relationship presaged a return of the monarchy. But his housekeeper Maria de Jesus was jealous, and Carolina’s son disapproved of the relationship.

The road to a continuing loving relationship had suddenly become too steep. Her surviving letters are eloquent of the pain she endured when she found that she had been dropped.

Christine Garnier (1951)

Salazar’s other nickname was “troca-tintas”, meaning he blew hot and cold. He earned this soubriquet because he was often conducting amicable relationships with more than one woman at the same time. If there were any sexual relationship with any of them, it is probable that any such relationship was serial, not contemporary.

The French Christine Garnier came to Portugal with the aim of writing a book not about Salazar and politics, but something more personal and, as it turned out, intimate. She captured Salazar’s affections, and on occasions managed to visit him in his official residence, in his holiday residence at Forte Santo António and even in the house where Salazar was born, in Vimieiro.

When he met Christine Garnier, Salazar was already 62 years old, but he was still in great physical shape and was still in full possession of his mental faculties, and he even changed lifelong behaviours. Instead of his habitual miserliness, he became a spender, and sent flowers, bottles of the best wines and other expensive gifts to the charming Christine. He even asked his close friend, Marcello Mathias, who was then ambassador to France, to buy a very valuable piece of jewellery in Paris as a gift for Christine Garnier.

One summer, when Christine Garnier was staying in the Forte de Santo António da Barra, Salazar’s summer residence, he realized that she rarely bathed and instead only smeared herself with lots of face and body creams. He became perturbed by her body odour. In those days, poor people rarely took baths, but despite his poor background, Salazar had high standards of personal hygiene. Salazar instructed the housekeeper, Maria de Jesus, to prepare a good soaking bath for his lady visitor, and witnesses saw her lugging successive buckets of hot water up the stairs for her bath.

Mercedes de Castro Feijó (1965)

Salazar later met Mercedes, who took the initiative to declare her love for him. Besides, because her father was an illustrious poet and Portuguese diplomat and her mother a Swedish aristocrat, Mercedes was in no way a woman to ignore. Salazar regularly visited her at her hotel in Lisbon, Hotel Borges in Chiado.

Respectable and decent hotels, such as Hotel Borges, took great care to protect their moral reputation. For example, ladies were not allowed to receive male visitors in their rooms and so it was with great astonishment that the elevator boy saw the President of the Council, with the respectful consent of the reception staff, climb into the hotel elevator to visit Mercedes de Castro Feijó in her rooms. The boy thought that the guest was sick, and that Salazar was going to medicate her. And, in a way, perhaps he was right.

It was Mercedes and Christine who nearly embarrassed him as they both appeared at the same time at the São Bento Palace, a near social disaster which he found very amusing.

Two children

Although Salazar had many romantic relationships and possibly lovers, he had no children. But he managed to experience the joys of fatherhood, as the housekeeper Maria de Jesus, with authorisation from the President of the Council, brought two of her nieces to live at the São Bento Palace. Salazar became fond of the girls and spent a lot of time with them. They became known as Salazar’s pupils.

Of these two girls, Salazar especially liked Maria da Conceição, nicknamed Micas. Micas arrived at Palácio de São Bento when she was six years old and lived with Salazar until she married at the age of 28. Despite scurrilous rumours of sexual interference, there is no evidence that he was anything but a normal loving father figure to both girls. Micas, in particular, retained fond memories of her time with him.

Conclusion

The accepted justification for his single status was that Salazar preferred to be married to his country, not to be distracted by domestic demands.

But perhaps he remained a bachelor so that he could conduct relationships with many different women. There is considerable evidence that he was an assiduous correspondent, and he must have spent hours in writing letters to the many women involved. There is no evidence that these women were jealous of each other, and they all remained loyal well after their time with him had passed.

Ultimately, the character of Salazar portrayed here is a complete contrast to the austere hermit that we thought we knew many years ago, when the country was subject to propaganda and censorship.

Salazar was widely detested for his political activity, but now that his love-life has been made public, the same cannot be said of the Salazar of romance. His single status allowed him relationships with many women, and although none managed to capture him in matrimony, they all remained faithful and discreet.

In his amorous activity, Salazar may even be a sympathetic character, and perhaps more Portuguese nowadays think to themselves, “Well, look at him! Single, and what a man!”

The story of Micas, and her relationship with Salazar is available here:

https://www.sabado.pt/StaticAssets/livros/35AnosSalazar.pdf

For those who wish to delve further into this subject: Os Amores de Salazar, Felícia Cabrita, Esfera dos Livros, 8th edition 2007. This book presents the more sensational and lurid possibilities of this subject.

By Peter Booker

|| features@portugalresident.com

Peter Booker co-founded with his wife Lynne the Algarve History Association.

www.algarvehistoryassociation.com