As the festive season approaches, Christmas lights illuminate the streets, and shops proudly showcase advent calendars and chocolate Father Christmases. Yet, amidst this familiar scene, Father Christmas isn’t the sole gift-giver around the world, as each country and culture has their own traditional gift-bringers.

The idea for this article first came to me as I have a Dutch friend who takes part in a Christmas charity event each year, where he dresses up as Zwarte Piet (Black Pete). Sinterklaas and Zwarte Piet are characters from Dutch and Belgian folklore associated with the celebration of St. Nicholas’ Day, which takes place on December 5 in the Netherlands. Sinterklaas is the Dutch version of St. Nicholas, a legendary figure known for his kindness and generosity, especially toward children, and Black Pete is his mischievous sidekick.

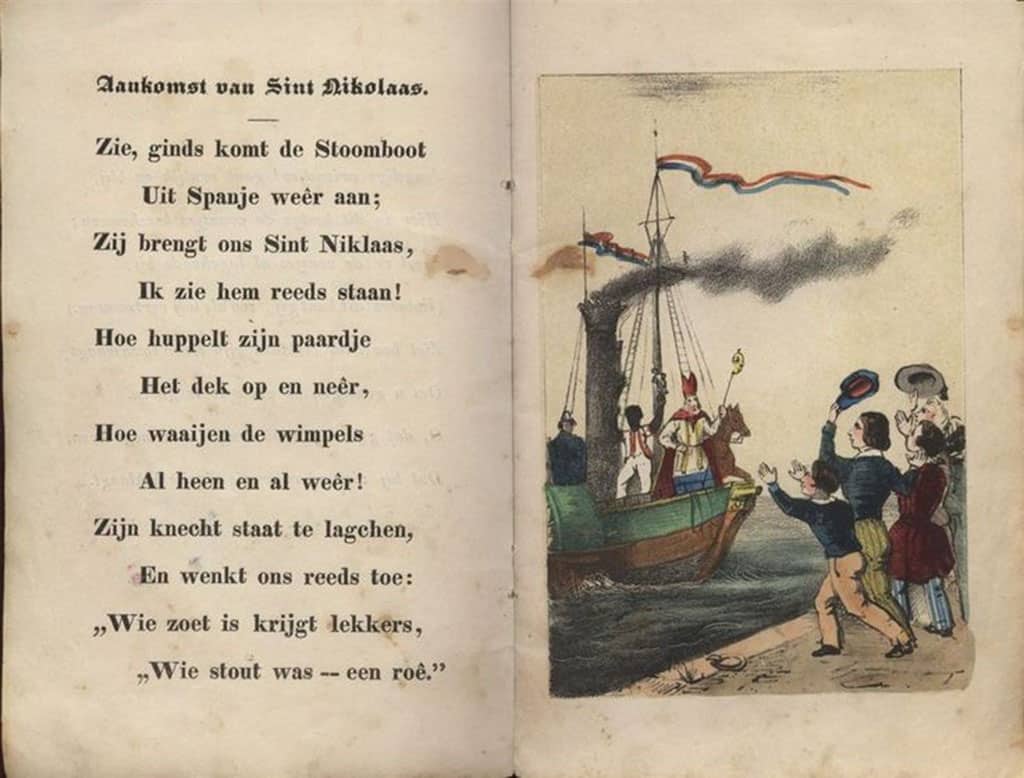

Traditionally, they arrive by steamboat from Spain in mid-November, and their arrival is a highly anticipated event which often includes a festive parade where they are greeted by crowds of excited children and adults. Sinterklaas is depicted as an elderly man with a long white beard, dressed in a red bishop’s robe and mitre, and holds a long ceremonial shepherd’s staff. Black Pete, on the other hand, is portrayed in colourful Renaissance clothing, with a black face, a curly wig, and red lipstick. Although, due to controversy, the character is now also commonly displayed with a few soot marks instead of the traditional black face.

Black Pete is also typically depicted carrying a bag containing candy for children, which he tosses around. Legend also has it that naughty children were put in that very same bag and taken back to Spain.

Another traditional gift-giver is Ded Moroz, which translates to “Grandfather Frost”, a winter deity in Slavic mythology, whom has been an integral part of Russian culture for centuries. Following the Soviet Union’s collapse, Father Christmas and other Western traditions started to gain popularity in Russia. However, during the resurgence of Russia in the early 21st century, the country placed a renewed emphasis on Ded Moroz, and even began sponsoring courses about the mythological character.

He is often depicted as an elderly, bearded wizard, wearing a long blue or red coat, a fur hat, and valenki on his feet (traditional Russian winter felt boots). He walks with a long magic stick and, instead of a sleigh pulled by reindeers, he travels in a troika (a traditional Russian sled pulled by three horses). He is also accompanied by his granddaughter and helper, Snegurochka, which means “Snow Maiden”. She is usually depicted as a beautiful, young girl with long silver-blue robes and a snowflake-like crown.

Both Ded Moroz and Snegurochka are prominent figures during the winter holidays, especially during New Year’s celebrations, which are more widely celebrated in Russia than Christmas. Families gather around decorated New Year trees, exchange gifts, and partake in festive meals to welcome the coming year. People who dress up as Ded Moroz and Snegurochka distribute the presents and fight off the wicked witch, Baba Yaga, who, according to legend, wants to steal the gifts.

Traditionally, Italy also has an interesting alternative to Father Christmas. According to Italian folklore, Befana is an old woman or witch who flies around on a broomstick on the night of January 5 (the night before Epiphany or Three Kings Day), delivering gifts to children throughout the country.

According to legend, the Three Wise Men stopped at Befana’s house on their way to see the baby Jesus. They asked her for directions, but she did not know the way and instead provided them with shelter for the night. She was said to be the best housekeeper in the village, with the most well-kept home, and the following morning, the Wise Men invited her to join them on their journey. However, she declined, saying she was far too busy with her household chores.

It is said that, later, Befana regretted not joining the Wise Men, and so she set out to find them. However, she was unable to locate them and, to make up for it, she decided to leave gifts for other children in the hope that one of them might be the baby Jesus. Therefore, every year on the night of January 5, Befana is said to travel around Italy, entering homes through the chimney and leaving small gifts and sweets for well-behaved children and a lump of coal for those who have been naughty.

Being the best housekeeper, she was also known to sweep the floor before she leaves. This is symbolically interpreted as sweeping away the problems of the previous year in anticipation of a better one. In return, families typically leave out a glass of wine and regional treats.

Further up North, Jólasveinar, also known as the Yule Lads, are mythical creatures and a part of the Christmas traditions in Iceland. These mischievous mountain-dwellers are said to be the sons of Grýla and Leppalúði, a pair of ogres who are also prominent figures in Icelandic folklore. The Yule Lads are their 13 sons and known to be a group of mischievous pranksters who steal from and harass the population. Yet, during the holiday season, they are said to come down to town, one by one, during the 13 nights leading up to Christmas, and leave small gifts in shoes that children have placed on windowsills. However, if children have misbehaved, they will find a potato in their shoe instead.

Lastly, we also have the Christkind, which translates to “Christ child”. The Christkind is still traditionally celebrated in parts of Europe, particularly in German-speaking countries, and can be traced back to Martin Luther in the 16th century. Luther wanted to shift the focus away from the Catholic figure of Saint Nicholas, who was associated with gift-giving, and bring it back to the celebration of the birth of Jesus. As a result, the idea of the Christkind as a symbol of the Christmas gift-bringer emerged and is usually depicted as an angelic-like child, with blond hair and wings, intended to be the embodiment of baby Jesus.

Whether you grew up with Father Christmas, follow the adventures of Zwarte Piet, or enjoy the angelic simplicity of the Christkind, one unifying thread emerges – the celebration of joy through the spirit of generosity. No matter the story or tradition, the holiday season is a celebration of the simple yet profound joy of spending time with loved ones.

|| features@portugalresident.com

Jay works for a private charter airline, and is also a UX designer and aspiring author who enjoys learning about history and other cultures