It is commonly asserted that Portugal´s international borders are the oldest in Europe. The Wikipedia entry on Portugal shows, “Founded in 1143, its current borders were established in 1297, among the oldest in the world.” About this claim, Evelyn Waugh might have written, “Up to a point, Lord Copper,” and while not exactly disagreeing, we might point out one or two inconsistencies.

In the first place, the small parish of São Felix de Galegos just to the north of Ciudad Rodrigo was indeed Portuguese under the Treaty of Alcanizes of 1297; but soon afterwards it became Castilian and is today known as San Felices de los Gallegos, indisputably a part of Spain.

Of far greater importance is the loss to Portugal of the county of Olivença. The Grupo de Amigos de Olivença operates as a patriotic society, open to all those interested in the Olivença issue, and its restoration to Portuguese sovereignty. This area of 430 square kilometres is not small, and the wonder is that it was ever Portuguese in the first place.

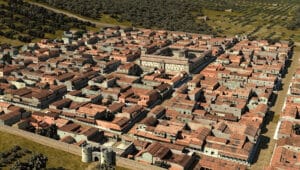

The Olivença territory on the eastern bank of the Guadiana River was awarded to the Templar Knights in the mid 13th century by King Alfonso IX of Castile and Léon. The Templars built a defensive wall around the new settlement which eventually became the town of Olivença, and it was transformed into a comenda, a territory which supported a Templar knight.

During the Reconquest of Hispania from the Moors in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, there was an agreement that the King of Castile and León would concentrate his efforts on the left, eastern bank of the River Guadiana, while the King of Portugal would concentrate his forces on the western bank.

When in 1297 at Alcanizes the two kings came to an agreement over their territories, Portugal gave up some territory on the east bank (including Aroche, Aracena and Aiamonte) but retained some other eastbank areas (including Olivença, Mourão, Barrancos, Moura, Serpa and Mértola). As the king at the time, D. Dinis (1279 – 1325), managed to hang on to territory on the far side of the Guadiana, he increased the territory under his control at the expense of the relatively hilly and remote Aroche and Aracena and other places on the other side of the river.

- Dinis and his successors, Afonso IV and later João II, built powerful defences at Olivença, including a castle, a tall keep and a ditch. D. Manuel I (1495 – 1521) ordered the old walls dismantled and the stone reused to build a stronger defensive wall. He also ordered the building of the Ponte da Ajuda over the Guadiana, a bridge of 450 metres, and 19 arches. If Olivença came under attack, a relieving force could quickly come over the bridge to its aid.

The Portuguese fortresses of Campo Maior, Elvas and Olivença formed a powerful defensive semicircle opposite the Spanish Badajoz, all of them guarding the main route between Lisbon and Madrid. It is probable that the Spanish monarchs found the elaborate defensive measures at Olivença together with the Ajuda bridge a threat to their border fortress of Badajoz.

Portuguese sovereigns in the eighteenth century consulted various international military strategists over the defence of Olivença. Their advice was remarkably uniform. They recommended that Portugal should abandon this territory to Spain, and their reasons were first that the expense in men, money and materiel was disproportionate to the value of the town; second that if the Ajuda bridge were damaged, it would be difficult to bring military aid to the town; and third that if the bridge were in Spanish hands, any Portuguese forces at Olivença would be surrounded.

During the Napoleonic wars, Spain took advantage of Portugal´s military weakness to neutralize the military threat of Olivença. In 1801, the Spanish Prime Minister Manuel de Godoy led a force to the border and invested Campo Maior and Elvas, and at the same time captured Olivença. He picked oranges at Elvas, and sent them to the Queen of Spain, Maria Luísa of Parma, and this small encounter thus became known as the War of the Oranges.

With the backing of France, Spain then imposed two treaties on Portugal in 1801, the first at Badajoz and the second at Madrid. Portugal was forced to concede Olivença to Spain and parts of Brazil to French Guiana. Once safely out of Europe in 1808, D. João the Prince Regent of Portugal published a manifesto in which he repudiated both treaties of 1801, maintaining that by the current invasion of Portugal, Spain had rendered them null and void.

Although at the ensuing Treaty of Vienna in 1815, after the second defeat of Napoleon, the European powers agreed that Olivença should be restored to Portugal, the Spanish representative demurred, and did not append his signature to the document until 1817. His objection was that Spain did not agree to restore Olivença to Portugal. In the meantime, Spain prohibited the use of the Portuguese language in this area.

Shortly afterwards, another difficulty arose. First Portugal and then Brazil chose to invade and annex the territory now known as Uruguay, and then known to Spain as Banda Oriental, and by Brazil as Provincia Cisplatina. Even as the Spanish Empire in Latin America was dissolving, Spain regarded this invasion as proof of Portuguese dissimulation and used it as an excuse to disregard the provisions of the Vienna Treaty.

In bilateral negotiations since 1815, Portugal has never agreed that the border between the two countries runs at the Guadiana, and modern Portuguese road maps do not show the international border between Olivença and Portugal. When in 1864, the two countries decided to cooperate in marking their common border from north to south, they found that they could not agree the border at Olivença. The Commission resumed its work in 1926, but only from the southern edge of the disputed border.

In addition, Spain has taken measures to increase the proportion of Spaniards in this territory by encouraging the immigration of people from other areas of Spain, and by hispanicising Portuguese street names and personal names.

Consider secondly the case of Gibraltar, which was conquered by an Anglo-Dutch force in 1704. In the peace negotiations at Utrecht in 1713, the Catholic King ceded the town and castle of Gibraltar in perpetuity to the Crown of Great Britain.

In what way is the situation of Olivença similar to that of Gibraltar? Both territories were invaded and conquered by another European power; both territories lost their indigenous populations and became identified with their conquerors; and both territories are now subject to claims from their erstwhile owners. In addition to these factors, there is the relatively new idea of democracy, the idea that the resident population should have a view on the destiny of their territory.

Yet after two hundred years of hispanicisation, there is no evidence that the people of Olivença would welcome a return to Portugal. And after more than three hundred years of British occupation and influence, there is little evidence that the people of Gibraltar wish to be reunited with Spain.

The advent of the European Union and the Schengen agreements have meant that international borders are less of a barrier than formerly, and that issues such as Olivença are less urgent than previously. While each territory remains subject to nationalist claims from the other side of its border, there is no reason to believe that the current state of affairs will ever change.

By Peter Booker

|| features@portugalresident.com

Peter Booker co-founded with his wife Lynne the Algarve History Association.

www.algarvehistoryassociation.com