I am a huge advocate of the digital age, having worked for many years with students using technical devices including tablets. However, personally, I have always believed that when it comes to reading for meaning and long-term recall, printed text produces far better comprehension and understanding.

Screen-based reading is dominating our everyday lives, specifically in education. Certainly, using online texts for schools is vastly cheaper, and easier to access. However, does it result in quality learning and understanding?

Should we be worried about our children’s reading comprehension when some schools have completely moved away from print to screen reading? In many cases, schools have turned their libraries into screen-based for all children, including Primary school-aged children.

Inevitably, research into this subject has been ongoing. Ground-breaking results about to be published worldwide now show that reading for understanding has dropped dramatically across the world for children from 11 years and above.

Whilst it is impossible not to assimilate this research with the long-term effects of Covid 19 and a worldwide lockdown, one cannot ignore that, if indeed onscreen reading was equal to paper-based, results would not have dropped so dramatically. Many schools and educational establishments have rushed into solely encouraging online reading and digital texts.

Neuroscientists are now able to show that deeper reading and understanding occurs when children read a book or text on paper than on a screen.

We must look at the human brain and begin to understand the difference between reading on paper as opposed to reading from a screen.

Reading is an abstract activity that is characterised by thoughts and ideas. In a simplified form: the human brain uses areas of the brain evolved to process vision and spoken language when reading a book. When reading, the brain connects this text on a page to a physical map, and words become a fixed location that are easily mapped and remembered.

When reading a paper book, a reader is able to create a very clear mental map. It has a uniform lay out, and a reader can focus on one page or paragraph without losing sight of the whole text. One’s senses are activated through the seeing of the words, the physical holding of the paper book and even from its smell. All of these factors result in the brain being able to process information effectively.

Screens are different: scrolling is needed to read an entire text and even e-readers are not equivalent to holding, touching, and engaging in a text in the same way as a printed text. As a result, information is not processed by the brain as effectively. It can also be shown that screen reading is more mentally and physically taxing on the mind.

As an educationalist, in a world that highly values lifelong learning and literacy, education and schools are increasingly propelled into an immersive technological age. It is essential that one takes time to stop and research the effects that this is having on our future lifelong learners.

It is vital to make informed choices and not to eradicate one simply because the other is cheaper, more accessible, and how the world is evolving.

Without a doubt, there is certainly a place for reading onscreen. Indeed, engineers, scientists and software developers are constantly researching and developing digital reading so that it more reflects and imitates the physical reading of a paper book.

Eventually, I am sure that it will almost reach that goal. However, not at the exclusion of the physical act of reading, and, ultimately, learning and understanding.

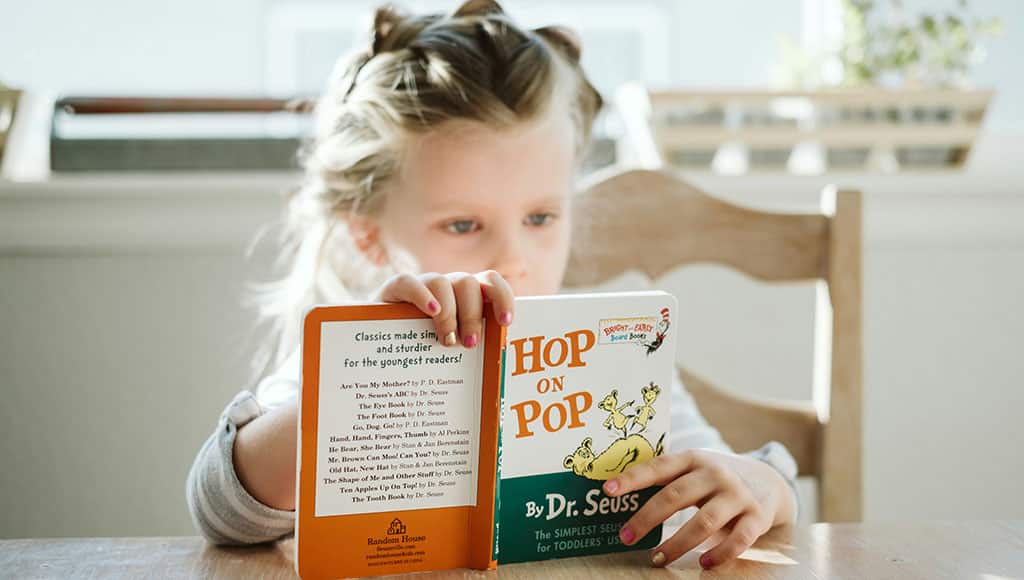

After all, who doesn’t want to snuggle up with the smell of paper and the feel of a book in their hands when they want to immerse themselves in a story?

‘The more books that you read, the more things you will know. The more that you learn, the more places you’ll go’ – Dr. Seuss

By Penelope Best,

International Education Consultant