The origins of the elf can be traced back to Norse mythology and Germanic folklore.

In these early tales, elves – or álfar – were otherworldly beings, closely tied to nature and gifted with magical powers. They were not the playful helpers we imagine today, but complex characters, ambivalent towards people and capable of either helping or hindering them. The huldufólk (hidden folk) of Iceland and the tomte or nisse from Scandinavia also share similarities with these early elves.

The huldufólk, described as elusive, human-like beings who live in harmony with nature, are said to inhabit rocks, hills, and other secluded areas, remaining hidden from plain sight. They are not malevolent but are known to fiercely guard both their privacy, intervening when humans disrespect the natural world. In modern-day Iceland, the belief in huldufólk is so strong that construction projects are occasionally altered to avoid disturbing their supposed dwellings.

The connection between the huldufólk and Christmas comes from Icelandic families gathering indoors during the darkest days of winter, sharing stories to pass the long nights. It is said that their presence is heightened around Christmas, as the winter solstice, marking the year’s longest night, is thought to thin the veil between worlds, making them more visible.

There are also many Icelandic folktales about the huldufólk invading farmhouses during Christmas to hold wild parties and feasts. For this reason, it is customary in Iceland to clean the house before Christmas and leave out extra food to ensure goodwill. These customs, aimed at appeasing the huldufólk, bear striking similarities to the traditions surrounding the Scandinavian tomte or nisse, who would later influence the image of the Christmas elf.

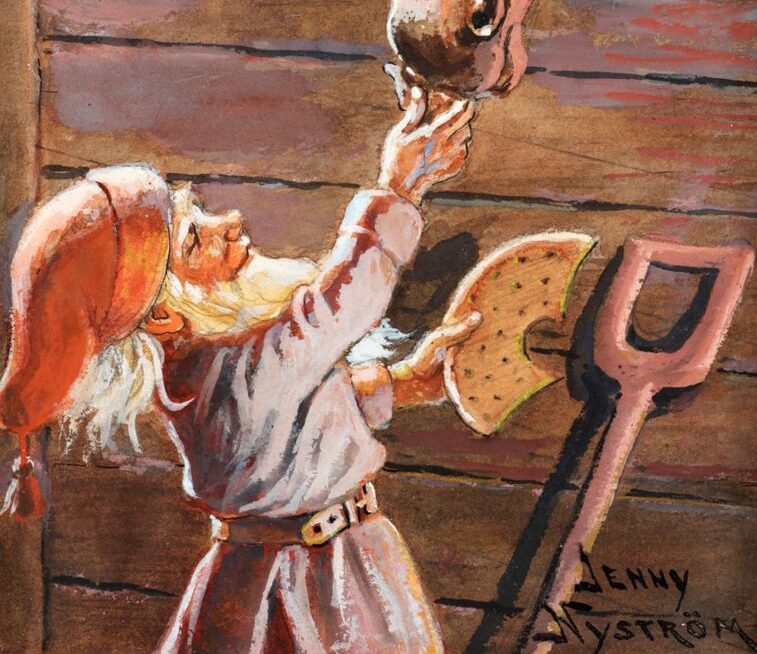

The tomte, in particular, plays a crucial role in bridging pagan traditions with the Christmas season. A solitary guardian of the farmstead, the tomte is often depicted as a small, elderly man with a long beard and a pointy red hat – similar to a garden gnome. They are said to watch over farms and families, ensuring the health of animals, the fertility of crops, and the safety of the household. However, they can also be mischievous or vengeful if they believe their owner hasn’t completed their tasks to tomte standards.

One of the most important Scandinavian customs on Christmas Eve was to leave out a bowl of porridge with butter for the tomte. Failing to do so – or, worse, skimping on the butter – could lead to trouble, such as livestock falling ill or chores going awry. Over time, as Christianity spread through Europe, these pagan spirits were adapted into the burgeoning Christmas narrative.

The eventual transformation of elves into Father Christmas’s helpers is a relatively modern development, shaped by 19th-century literature and the commercialisation of Christmas. In 1823, Clement Clarke Moore’s poem A Visit from St. Nicholas (commonly known as The Night Before Christmas) introduced Father Christmas as “chubby and plump” and “a right jolly old elf”. Though Moore’s Father Christmas was himself the elf, the imagery of small magical beings working in tandem with St. Nick began to take shape.

Later, in the mid-19th century, American writers and illustrators further developed the concept of the Christmas elf. This image was popularised by Godey’s Lady’s Book (an American women’s magazine), which featured an illustration on its 1873 Christmas cover, showing Father Christmas surrounded by toys and elves. This depiction, influenced by the Industrial Revolution, reflects a time when society was captivated by the innovation of factories and mass production, blending these ideas with the magic of Christmas. Godey’s was a major influence on Christmas traditions, even publishing the first widely circulated image of a modern Christmas tree on its 1850 cover.

Furthermore, illustrations featured in Harper’s Weekly by Thomas Nast, considered the Father of the American Cartoon, portrayed Father Christmas’s workshop at the North Pole, staffed by industrious elves crafting toys for good children. By the end of the century, the image of the Christmas elf as a cheerful, hardworking assistant to Father Christmas had firmly cemented itself in the public imagination.

In recent years, the concept of the “Elf on the Shelf” has also brought a mischievous twist to the tradition. Based on a 2005 children’s book by Carol Aebersold and Chanda Bell, these modern elves are sent from Santa to monitor children’s behaviour. Each night, they report back to the North Pole, and each morning, they appear in a new location – often caught in humorous or playful acts.

This modern twist draws on the original lore of elves as mischievous creatures while adding an interactive touch to the Christmas season. For parents, it’s a way to engage children in the holiday spirit; for children, it’s a reminder of the magic that lies just beyond the visible world.

The Christmas elf’s evolution – from mythological beings to workshop assistants, to modern-day mischievous creatures – mirrors the world’s own changing relationship with the holiday. Still, they serve as a reminder of the lasting power of storytelling and the value of keeping traditions alive while welcoming new ideas and interpretations.

|| features@portugalresident.com

Jay works for a private charter airline, and is also a UX designer and aspiring author who enjoys learning about history and other cultures