Salt was once a precious commodity. Today, it has become so common that we reach for it without hesitation.

It’s sprinkled on our eggs in the morning, tucked into caldo-verde at lunch, and rests on the rims of margarita glasses at night. However, long before electricity and supermarkets, salt held a sacred place in society. It preserved meat, cured fish, and the ancient Egyptians even used it to protect bodies from decay. The Via Salaria, an ancient Roman road, existed solely to transport salt across the empire, and in the Hebrew Bible, salt was used to seal covenants with God – an unbreakable bond, known as the covenant of salt.

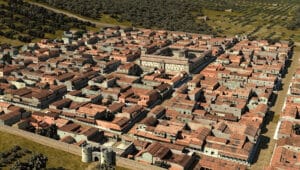

In Portugal, salt’s significance is as old as its coast. With a long Atlantic shoreline, warm sun, dry winds and shallow coastal plains, the country’s geography made it an ideal setting for sea salt production. Long before Portugal existed as a nation, the Phoenicians and Carthaginians were already extracting salt from the tidal marshes of the south. However, it was the Romans who turned salt into a structured trade.

The Romans built salt pans along the Atlantic, including in what is now the Algarve, to supply their legions and markets with salted meats and fish. Roman troops stationed across the Iberian Peninsula often received salt rations as part of their compensation. So essential was this mineral that it earned the name “white gold.” The Latin word for salt, sal, also gave rise to salarium – a word we now recognise as “salary.” This referred to the amount of money a soldier was given to buy salt.

As the Roman Empire faded, salt production never stopped. During the Middle Ages, salt was among the most heavily taxed and controlled substances in Europe. In Portugal, it became one of the crown’s most strategic commodities. During the 13th century, King Afonso III took state control over salt production and trade, recognising its value not only in feeding his people but in funding his government. Monopolies on salt were granted to towns and guilds, and prices were carefully regulated. To control salt was to control wealth and political leverage.

By the 15th century, when Portugal was beginning its seafaring expansion into Africa, Asia, and the Americas, salt again played an important role. Portuguese ships needed preserved food to survive the long and treacherous journeys into unknown waters. Cod, fished in the North Atlantic, was brought to Portuguese shores and preserved with the country’s abundant salt before being stored in the hulls of ships. Without salt, the Age of Discovery might never have happened.

Salted cod soon became a staple of the Portuguese diet, not only for sailors but for the general population. Its affordability, long shelf-life, and versatility meant it could feed a growing urban population, sustain rural communities, and meet the fasting requirements of the Catholic Church, which forbade meat on numerous days of the year. Portugal’s mastery of fish preservation gave it an edge in both nutrition and trade. Salt wasn’t just preserving food – it was preserving the reach of an expanding maritime empire.

Salt extraction, especially from the south, began to define the landscape. The Algarve, particularly towns like Castro Marim, Tavira, and Olhão, became major centres of production. Their salt pans – flat, mirror-like pools arranged in geometric patterns – sustained generations of families and gave rise to local economies that still persist today. Workers used age-old methods: guiding sea water into shallow basins, letting it evaporate under the summer sun, then raking and piling the salt. These salt pans also became ecological refuges where flamingos, herons, and storks rest and feed in the same waters from which salt is drawn.

Further north, in places like Aveiro and Figueira da Foz, salt production also took root. Known as the “Venice of Portugal,” Aveiro developed a salt-based economy supported by canals and small boats – moliceiros – that transported salt across town. The salt from these regions served not just local use but was traded across Europe and Portuguese colonies. Salt warehouses – armazéns de sal – still stand today as monuments to that past.

In the centuries that followed, industrialisation and modern food preservation methods gradually reduced salt’s role as a strategic commodity. Yet Portugal continued to produce high-quality sea salt, preserving centuries-old techniques. In the 21st century, as consumers turned back to artisanal and natural products, Portuguese salt – especially flor de sal from the Algarve – regained recognition for its purity, texture, and taste. What was once traded by kings and rationed to soldiers now graces the plates of chefs and home cooks alike. In this way, Portugal’s salt continues to season not just food, but the story of a country bound to the sun and the ocean.