Of all the months in the year, February stands apart – not only for its short length but for the fascinating history that shaped it. While every other month boasts at least 30 days, February has a mere 28, occasionally gaining an extra day every four years.

To understand why, we must look back to a time when Roman rulers, priests, and astronomers shaped the calendar around lunar cycles, political ambitions, and ancient superstitions.

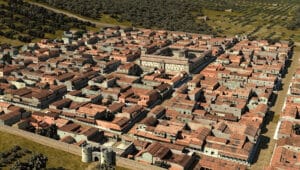

The original Roman calendar, attributed to Romulus, the legendary founder and first king of Rome, served as a practical tool for an agrarian society.

Beginning in March and ending in December, it consisted of only 10 months and totalled 304 days, with no official recognition of winter.

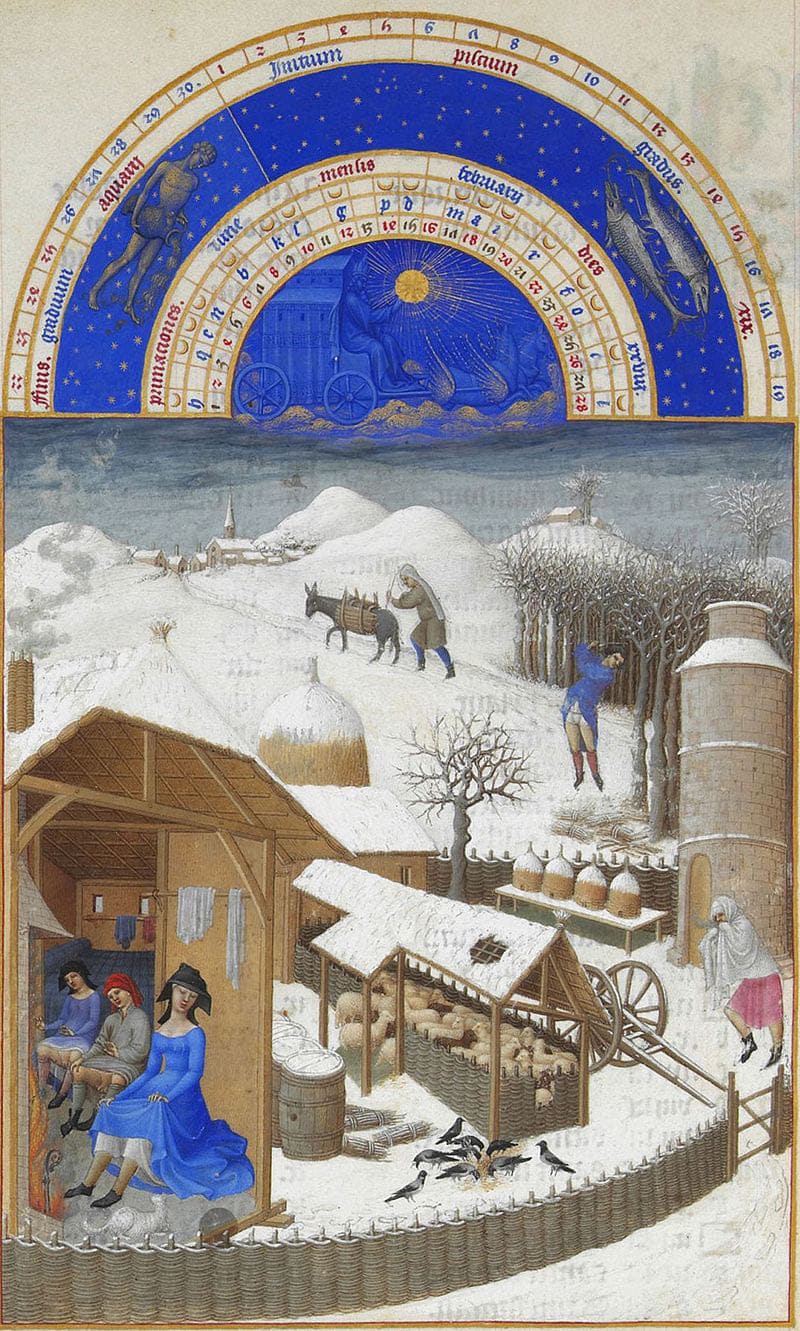

During this cold season, when nothing could be planted or harvested, the year effectively “paused” for around 60 days, only to restart with the arrival of March, when warfare and agricultural activities resumed.

This early system also explains why some of our modern months seem misnamed – September, October, November, and December derive from the Latin words for seven (septem), eight (octo), nine (novem), and ten (decem), reflecting their original places in the Roman year. However, their positions were eventually pushed forward by later reforms.

It was Numa Pompilius, Rome’s second king, who recognized the need to fill the awkward winter gap. He restructured the calendar by adding January and February, extending the year to 12 months and aligning it with the lunar cycle. Given the Romans’ superstition about even numbers being unlucky, the months were adjusted to have 29 or 31 days.

Furthermore, since a lunar year is 354 days long (an even number), he also added an extra day to create a total of 355 days in the calendar year. This, however, posed a mathematical dilemma – because 355 is an odd number, at least one month had to contain an even number of days.

February, placed at the end of the year, was already linked with honouring the dead, particularly during Parentalia, when families visited tombs, left offerings of flowers, wine, and bread, and held feasts in memory of their ancestors. Given its already solemn nature, February was the month chosen to have 28 days. After all, what could be more unfortunate than death itself?

However, the lunar calendar presented its own challenges for the Romans. The lunar year is 10 days shorter than the solar year, causing misalignment with the seasons dictated by the Earth’s orbit around the sun. By the time Julius Caesar came to power, the Roman calendar was completely misaligned.

Recognising the need for a more accurate calendar system, Caesar replaced the Roman lunar calendar with a solar calendar modelled after the Egyptian system. During his time as a military leader and later as a statesman, he spent considerable time in Egypt, especially during his famous relationship with Cleopatra.

It was during this period that he came into direct contact with Egyptian scholars, astronomers, and diplomats, renowned for their expertise in astronomy and timekeeping.

Drawing from their system, Caesar implemented a new calendar that set the average year length to 365.25 days, incorporating an extra day for February every four years to correct the discrepancy. With this reform, the Julian calendar was born.

The length of February has since become a topic of myth and speculation. One popular legend claims that its short length is due to Augustus’ vanity. The story goes that when the month Sextilis was renamed Augustus in his honour, it originally had only 30 days, one fewer than Julius (July), named after Julius Caesar.

Augustus, also known as Octavian, determined to solidify his legacy and ensure that his month did not appear inferior to that of his great-uncle, supposedly “stole” a day from February, adjusting it to 28 days and making his month 31 days long.

While Caesar’s calendar brought much-needed order, it was not perfect. A slight miscalculation – just 11 minutes per year – caused the dates to slowly drift out of sync with the seasons, accumulating an extra day every 128 years.

To fix this, Pope Gregory XIII introduced the Gregorian calendar in 1582, refining the leap year system to maintain better alignment with the Earth’s orbit. Yet, despite all these adjustments over the centuries, February remains the odd month out – a lasting remnant of Rome’s ancient superstitions.