For thousands of years, people have followed rituals to ward off misfortune or summon good luck. Many of these customs involve wood – a material long associated with life, power, and protection.

In Norse mythology, the first humans, Ask and Embla, were shaped from wood by the gods and given flesh and spirit. According to legend, they were once lifeless driftwood, washed ashore until Odin and his brothers, Vili and Vé, breathed life into them.

The Celtic, Germanic, and Slavic peoples carved protective symbols into wooden objects or carried wooden talismans to shield themselves from bad luck. Celtic priests, in particular, revered trees like the oak and ash, believing them to be dwelling places of gods and spirits. Touching these sacred trees was thought to offer divine protection and guidance – a belief that has endured in the simple act of knocking on wood.

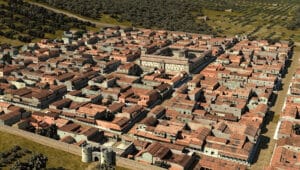

The Greeks and Romans also held trees in high regard, associating them with the divine and the supernatural. The oak tree was sacred to Zeus, ruler of the gods, and at the Oracle of Dodona, priests interpreted the rustling of its leaves as messages from Zeus himself. Visitors traveled great distances to consult the oracle, where priestesses known as Peleiades would listen to the wind whispering through the trees and deliver prophecies.

Similarly, the laurel tree, dedicated to Apollo, played a central role in religious life. Laurel wreaths crowned victorious athletes, military commanders, and poets, symbolising both their triumphs and divine favor.

During the medieval period, European societies developed an acute fear of tempting fate. Speaking too openly of good fortune was thought to invite disaster, and knocking on wood became a way to counteract this perceived risk.

As Christianity spread, the ritual took on deeper meaning. Some Christians linked the act to the wood of Christ’s cross, seeing it as a subtle invocation of divine protection – akin to a whispered prayer, a way to seek safeguarding without drawing attention.

By the 1800s, the phrase “knock on wood” (or “touch wood” in Britain) had become firmly embedded in everyday speech. What began as a ritual act evolved into a common expression, appearing in books and sayings throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Today, people across the world still knock on wood – some out of habit, others out of a lingering, almost instinctive belief in its protective power.

In Portugal, people practice “bate na madeira” (literally “knock on wood”), often knocking three times on the nearest wooden surface after mentioning a potential misfortune.

Variations of this tradition exist worldwide. In Turkey, people pull on one earlobe and knock on wood twice to ward off bad luck. In Italy, the phrase “toccare ferro” (“touch iron”) serves a similar purpose, reflecting a cultural preference for metal as a protective force.

The exact origins of the superstition remain uncertain, but several theories attempt to explain its widespread use. One suggests it stems from a 19th-century children’s game called Tiggy Touchwood, a variation of tag in which players were immune from being tagged if they touched a piece of wood – such as a tree or door.

The game was widely played in Britain and may have influenced English-speaking cultures, reinforcing the idea that touching wood could offer protection, even beyond the playground.

Another theory links the practice to the persecution of Jews during the Spanish Inquisition. Many synagogues were constructed from wood, and the community developed a secret system of coded knocks to gain entry, ensuring the safety of those seeking refuge.

Sailors, too, may have contributed to the tradition. Wooden ships carried them across treacherous seas, and knocking on the wooden decks was possibly a ritual to ensure safe passage.

Given Portugal’s maritime history and its explorers who braved the unknown aboard wooden vessels, the connection between knocking on wood and seeking protection from the perils of the ocean seems particularly relevant.

Similarly, miners, reliant on wooden supports deep underground, were known to knock on beams to test their stability – perhaps another way the practice took hold.

Whether to avert bad luck, express gratitude for good fortune, or simply out of habit, knocking on wood endures as a small but meaningful ritual. Across cultures and centuries, wood has remained a symbol of life, protection, and the sacred.

In that brief, instinctive tap on a wooden surface, we attempt to assert some control over uncertainty – offering ourselves a moment of comfort in a world where luck plays its part.